Additional Information

In his 1940 press release calling for competitive entries, Noyes wrote: “In the field of home furnishings there has been no outstanding design developments in recent years. A new way of living is developing, however, and this requires a fresh approach to the design problems and a new expression. An adequate solution which takes into consideration the present social, economic, technical and esthetic trends is largely lacking.” It went on to point out that the young designers who might conceivably address these issues worked at a considerable disadvantage because “they have not opportunity to form the contacts with industry which would enable them to have their designs produced.”

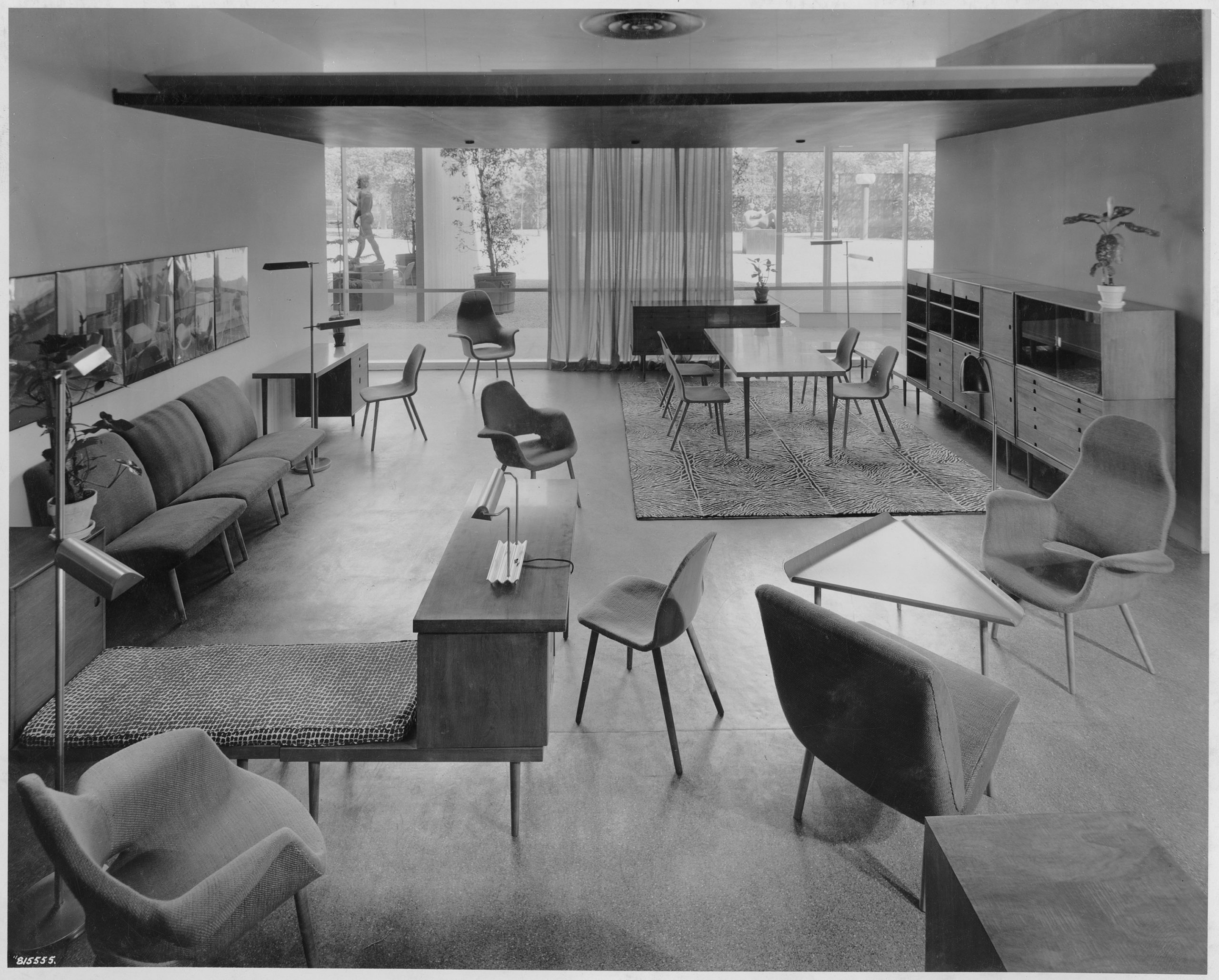

The competition addressed this. Several manufacturers agreed to produce the prize-winning designs, and a consortium of retailers (led by Bloomingdale’s department store in New York) agreed to sell them. Thus, the winner of the competition would have guaranteed distribution. The contest drew over 1,000 entries and captivated minds around the country and was received most enthusiastically at The Cranbrook Academy of Art. Charles was then head of the Industrial Design department. The school was run by architect Eliel Saarinen, aided by his son Eero Saarinen, also an architect and Charles’s best friend.

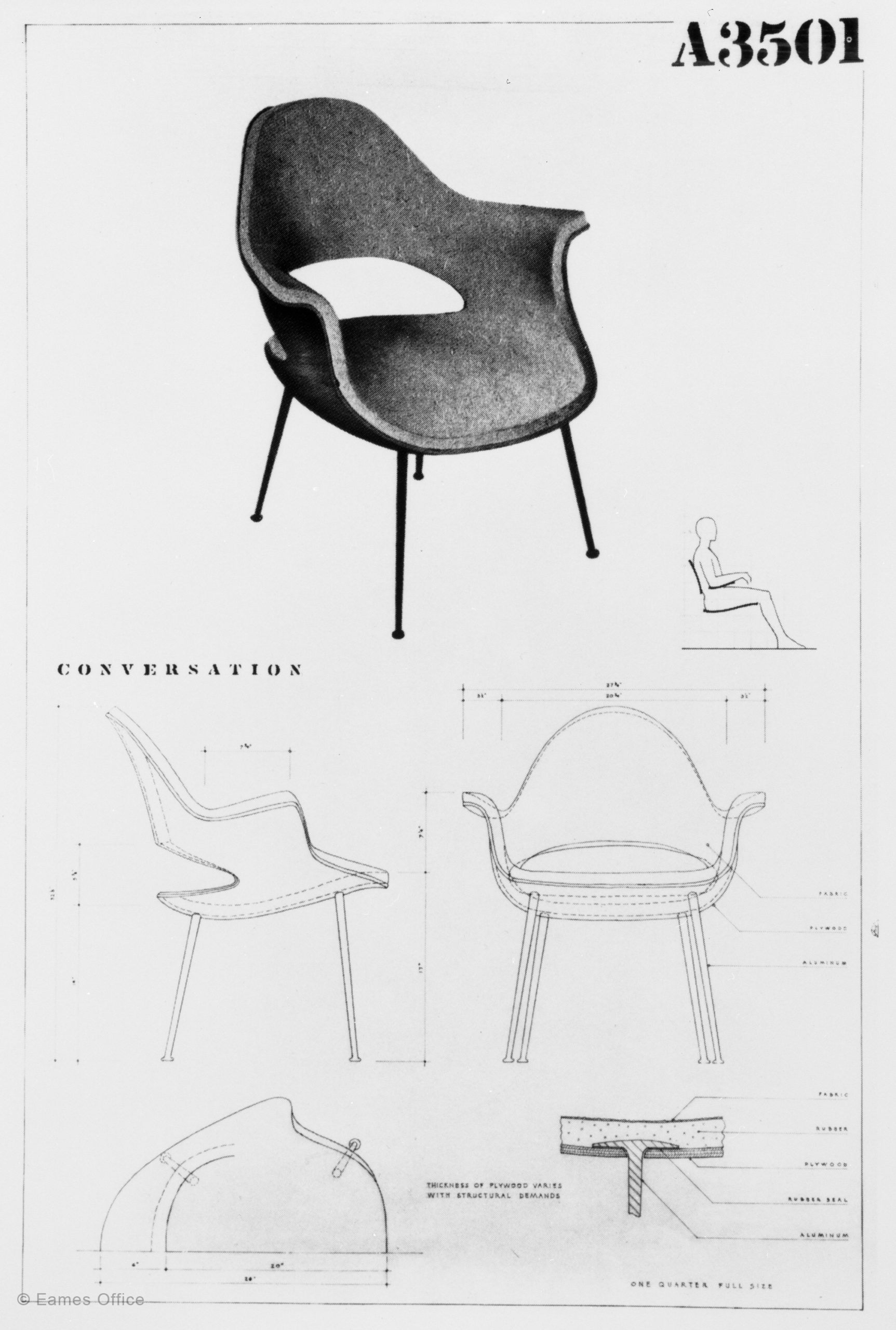

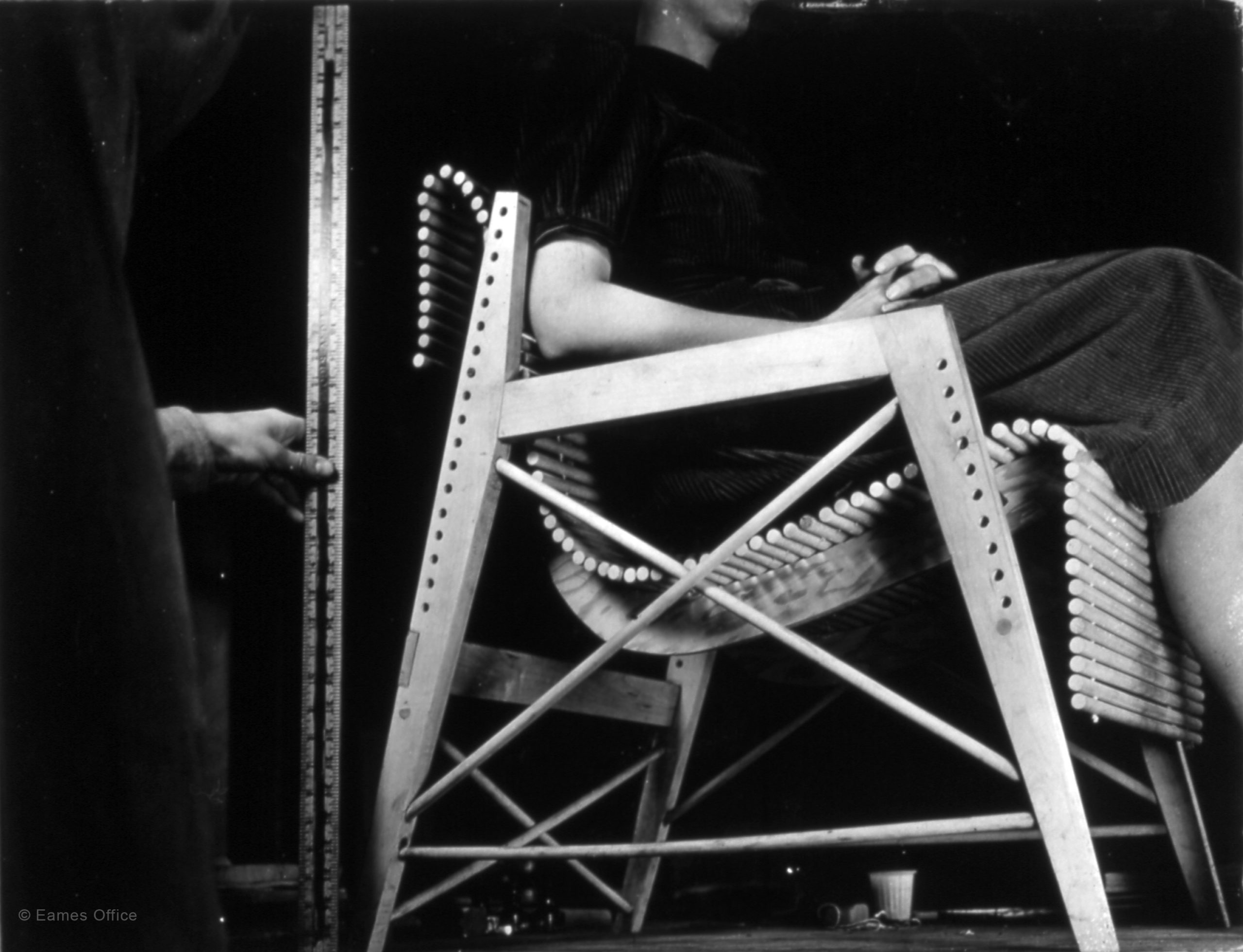

Thick cushions or springs and wads of stuffing were used with most furniture of this era, and the chairs had little flexibility. Charles and Eero’s big idea was to apply what Charles would call “an architectural solution” to the problem of seating. To apply architectural thinking meant that they would shape the chair to provide support and thereby do away with the need for thick padding.

They conceived of plywood shells, molded with compound curves, and to provide the desired height, thin aluminum legs. The legs would be attached to the plywood shells by rubber shock mounts, inspired by the rubber shock mounts of car engines. The molded wood shells gave support to the sitter, the rubber shock mounts gave the chair flexibility for added comfort. The designers hoped to make the shell’s compound curves as uniform as possible and create them in the wood itself.

Ray Kaiser (soon to be Eames) was on the scene at Cranbrook, auditing classes. Ray helped some with the final presentation drawings. It was around this time that she and Charles began their personal relationship as well. He remembered that Charles would ask anyone in hailing distance to try the chair out. Charles would watch carefully to see how they were reacting and experiencing the chairs. In the end, Charles and Eero settled on four chairs and three tables, and five case goods.

The entry, including drawings and photographs of the scale models, went off to New York. At the end of January, 1941, the announcement came: Charles and Eero had won first place in both seating and case goods! Though the form of the organic chair is the most arresting aspect of the chair visually and in terms of the mass production challenge, the judges cited another innovation which was the use of a flexible leg mount to provide a kind of springy feel.

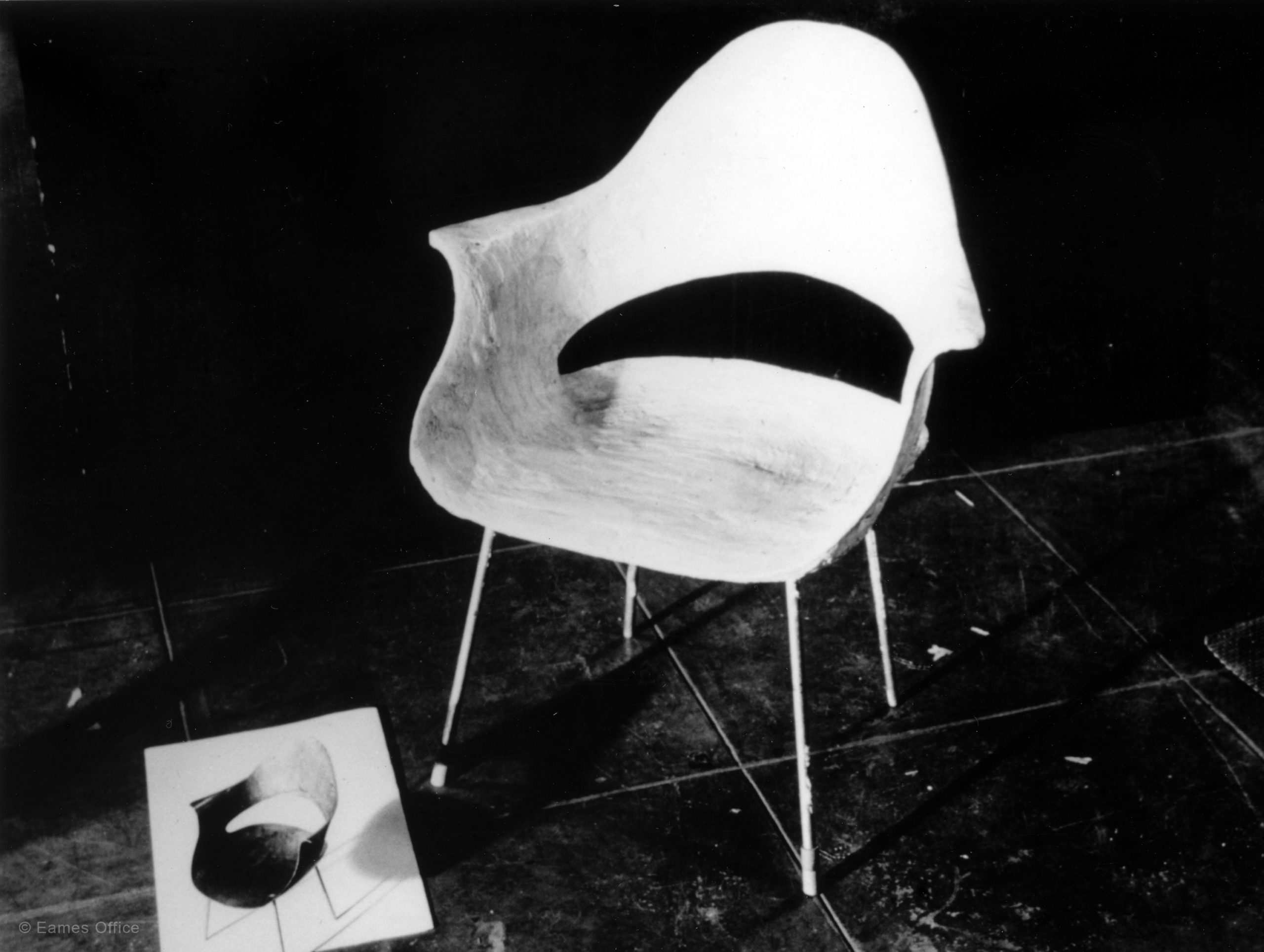

Now Eames/Saarinen team had to deliver, and so far, they had only plans and a few models. Their models and Charles’ photographs had been so persuasive that people asked if they already had full-blown chairs–which they did not. The chair mock-up took longer than expected, while tables and case goods proved to be less of a problem. But the chairs were a different matter. That same April the first wooden shell was finally created–to no one’s satisfaction.

Eames and Saarinen had hoped to mass-produce the plywood shells, but the technology didn’t yet exist for this. When they attempted to create curves in the plywood, the standard industry furniture presses produced splintered wood. They hoped to allow the wood surfaces to be expressed, and to some extent, they achieved this with the back of the relatively simple form of the side shell chair. But the armchairs required too much molding than they could manage, and they ended up covering the glued-up plywood shells with upholstery on the front and back.

Restrictions on materials imposed by a government readying itself for what became World War 2 meant that the thin aluminum legs had to be replaced by thick, solid wood dowel legs. Even with these enforced compromises, the Organic Design seating was surprisingly lightweight, especially when compared to traditional upholstered furniture.

“I suppose Eero has told you of our finally getting around to some cast iron dies. It makes me sick that we didn’t insist on giving it a trial months ago.” In other words, more problems with the actual tooling. Indeed, each individual chair shell required a great deal of work in all sorts of ways. After the molding process, the wood was splintered and necessitating the unsatisfactory concealment with fabric. In other words, the organic chair, intended as an expression of the potential of mass-production, had, as Ray later noted, “become a handmade object” all over again.

Charles Eames to Eliot Noyes

The verdict on the program was a mixed positive: good works were created, and new designers were discovered and given meaningful experience with manufacturers; on the other hand, mass-production was not achieved in any meaningful sense for the Eames/Saarinen shell chairs. The exhibition itself offered an interesting allegory. Noyes exhibited a traditional easy chair in a barred cage like King Kong (there was a Gargantua poster behind it). Like one found at a zoo or natural history museum, the label read, “Cathedra Gargantua, genus Americanus. Weight when fully matured, 60 pounds. Habitat, the American Home. Devours little children, pencils, fountain pens, bracelets, clips, earrings, scissors, hairpins and other small flora and fauna of the domestic jungle. Is rapidly becoming extinct.”

If the extinction of traditional furniture was imminent, it would not be at the hands of the modern chairs in that room, but it might come through their descendants. Charles had clearly learned that if you were designing for mass production, you had to discover how to make the tooling — not just the end product — yourself.

Bloomingdale’s featured the designs in their catalog, and even with the advent of World War 2, they were also exhibited for sale at several other department stores around the country in early 1942. This was the

last year in which the original examples were produced and sold.

Our partner Vitra brought back the Organic Seating in the early 2000s. We are pleased that our contemporary customers can enjoy the pleasures of these revolutionary chairs.

Explore Similar Works

Related Products

Browse a curated selection of Eames Office products we think you’ll love